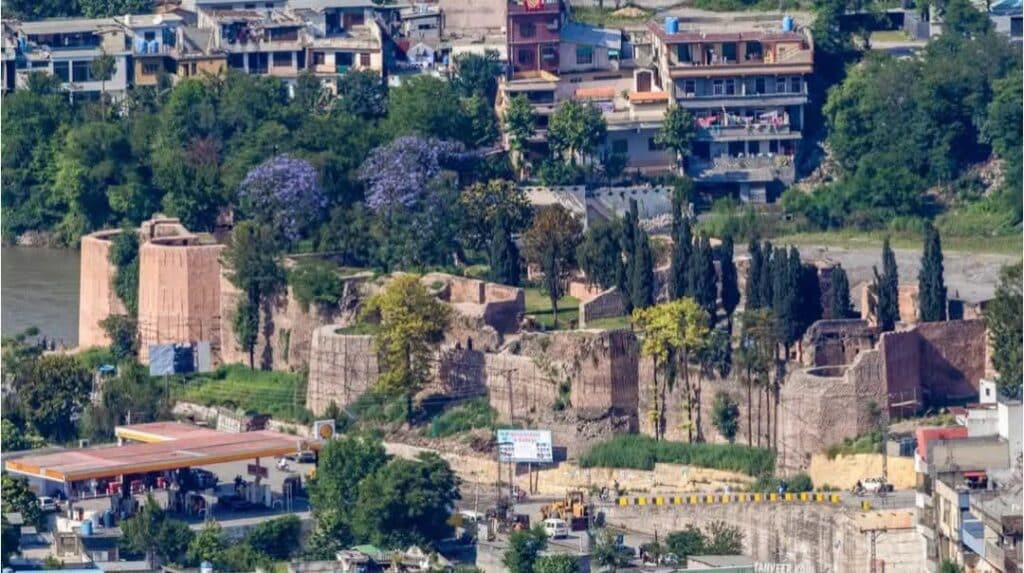

MUZAFFARABAD, Azad Jammu & Kashmir (PaJK)—From the bend in the Neelum River, it looks less like a monument and more like a geological fact. The reddish-brown walls of Muzaffarabad’s Red Fort rise from the bedrock, merging with the cliff face as if carved by the river itself.

For nearly five centuries, this citadel has not merely stood; it has witnessed. It has watched empires march, borders harden, and the very river that once defended it slowly eat away at its foundations. Today, it stands as perhaps the most potent, if crumbling, physical archive of Kashmiri history in the region’s capital.

This is not a story of frozen architecture. It is a chronicle of adaptation, survival, and silent testimony. The Red Fort’s stones hold the ambitions of the Chak dynasty, the administrative chill of the Mughals, the martial stamp of the Durranis, and the heavy hand of the Dogras. Its current state—a mix of melancholic grandeur and visible decay—poses urgent questions about heritage, memory, and what a community chooses to preserve.

Strategic Birth on a Contested Frontier

Our story begins in 1549, in a world of shifting suzerainties. The independent Chak rulers of Kashmir, their kingdom a jewel coveted by the expanding Mughal Empire to the south, faced a perennial threat. Their response was one of strategic genius.

They chose a spit of land where the Neelum River (then called the Kishan Ganga) hooks sharply, creating a natural moat on three sides. Only a narrow land bridge connected it to the city. “They weren’t just building a fort; they were sculpting a dilemma for any invading force,” says Dr. Arif Malik, a historian focusing on Himalayan architecture. “Attack from land, and you face a bottleneck under the fort’s walls. Try the river, and you’re exposed and battling the current. It was a defender’s dream.”

Built by local artisans with massive, rounded river stones, the original fort was a purely military organism—a place for garrison, storage, and imposing control over the trade route along the river.

A Chameleon Under Empires

History, however, has a way of repurposing symbols of power. With the Mughal annexation of Kashmir in 1587, the fort’s stark military purpose faded. The empire’s frontiers lay far to the northwest. The fort was demilitarized into a royal serai—a luxurious lodge for Mughal elites on their famed pilgrimages to Kashmir’s gardens. “It became a destination, not a deterrent,” notes Malik. “The echoes in its courtyards changed from the clang of arms to the discussions of courtiers.”

This interlude was brief. The Afghan Durrani Empire, which seized control in the mid-18th century, saw the region’s value anew. Under Sultan Muzaffar Khan—the city’s namesake—the fort was expanded and re-fortified, its walls thickened for a new era of conflict.

The most transformative—and, for many Kashmiris, most painful—chapter came with the Dogras in the 19th century. For Maharajas Gulab Singh and Ranbir Singh, the fort was the key to holding Muzaffarabad, the western gateway to the Vale of Kashmir. They renovated it extensively, using it as an administrative nerve center and garrison to consolidate their often-brutal rule.

It is here that the fort’s darkest spaces speak loudest: a labyrinth of eight subterranean dungeons, cells of damp brick and perpetual shadow. “These kāl koṭhṛīs (black cells) are not Mughal or Afghan; their construction is Dogra,” explains a local archaeologist who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of historical interpretation. “They are the physical infrastructure of control. You can feel the weight of that history in the cold air.”

The Assaults of Earth and Water

The Dogras left in 1928. For decades, the fort slumbered, a haunted place slowly ceded to the elements, until it was handed over to AJK’s Department of Archaeology.

Then, nature delivered its own sieges.

The 1992 floods were a warning. The 2005 Kashmir earthquake was a cataclysm. The 7.6-magnitude tremor shattered walls, collapsed entire sections facing the river, and severely damaged a small on-site museum, scattering or burying its artifacts. The outer sarai (travelers’ inn) was reduced to rubble.

But the most insidious enemy is constant: the Neelum River itself. The very waters that defined its strength are now eroding its being. Annual floods, exacerbated by climate change and upstream environmental shifts, gnaw at the foundations. A 2010 flood was so severe it prompted the construction of a large protective embankment—a stark, modern wall now guarding the ancient one.

“It’s a race against time and hydrology,” the site’s longtime caretaker, Muhammad Farooq, tells me, gesturing towards the river’s edge where stonework has recently vanished. “The river is hungry. Every monsoon, we hold our breath.”

The Present: Picnickers, Plans, and a Precarious Future

Today, the fort is a park. On a sunny afternoon, families picnic in its weathered courtyards, children chase pigeons through arches that once framed marching soldiers. It is a space reclaimed for casual joy, its grim past softened by samosas and laughter. Yet, this very normalcy masks a precarious reality.

The conservation challenges are immense. “This isn’t a simple restoration,” says Farooq. “It requires geotechnical engineering to stabilize the riverbank, archaeological expertise to guide rebuilding, and significant, sustained funding.” He confirms that restoration blueprints exist with the Department of Archaeology, but the leap from plan to action, always slow, has been stalled by bureaucratic and financial hurdles.

The fort thus exists in a liminal state—between memory and oblivion, between being a protected heritage site and a slowly disintegrating landmark.

The Unyielding Stone

To walk through the Red Fort today is to take a palimpsest tour of Kashmir’s soul. It is all here: the indigenous shrewdness of its founding, the imprint of continental empires, the trauma of subjugation, the resilience in the face of natural disaster, and the quiet, daily reclamation by the people who live in its shadow.

Its value for an independent Kashmiri audience, and for the international community, is profound. It is evidence. In a region where history is often contested or erased, the fort’s stones are stubbornly factual. They tell a contiguous story of strategic importance, of adaptation, of suffering, and of endurance.

The planned restoration is not merely a technical task. It is a moral and political one. Will this archive in stone be preserved? Will the dungeons be contextualized, the Mughal lodgings explained, the Chak craftsmanship celebrated? Or will it continue to weather away, its stories lost to the river?

The Red Fort has withstood conquerors. It has withstood earthquakes. Its final test may be against the silent forces of indifference and the relentless flow of time. For now, it refuses to fall, a silent, scarred sentinel keeping watch over the Neelum, insisting, against all odds, on being remembered.

Submit Your Story

Let your voice be heard with The Azadi Times